Upon entering the first room of The Sun Falls Silently, Thao Nguyen Phan’s exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, an idea seized me. Since Plato—or perhaps even earlier—the cave has stood as a metaphor for ignorance, concealment, even barbarism. It is an architecture of shadows, a chamber of falsehoods, opposed to the surface, to light, to truth. But who decided the cave must be a prison of illusions? Why not see it instead as a place of questioning, a ground for new ideas?

This exhibition—the artist’s first solo show in France—brings together a wide range of works: videos, slide projections, watercolors, sculptures, and installations. Born in Vietnam in 1987, Thao Nguyen Phan studied at the Ho Chi Minh City University of Fine Arts before continuing her education in Singapore and later in Chicago, where she graduated in 2014. After years abroad, she returned to Ho Chi Minh City, where she now lives and works. This decision reflects her deep commitment to exploring Vietnam’s history, its people, and broader questions of nationhood, belonging and “modernity”.

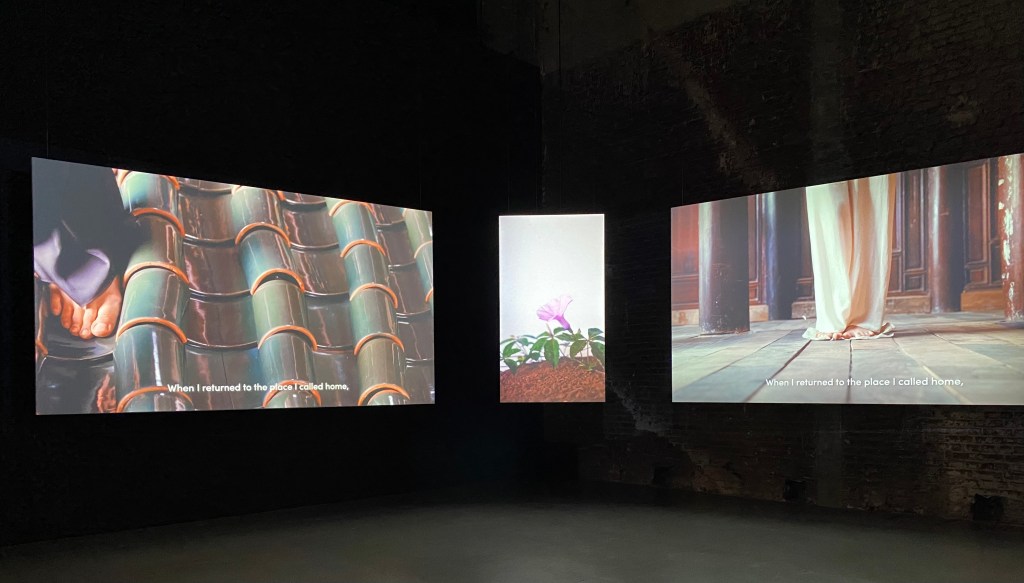

The main room, cavernous in its atmosphere, houses Reincarnation of Shadows, a five-channel video installation tracing the life of Diem Phung Thi, a dentist who became a sculptor at the age of forty. The work follows her journey from a childhood in the mountains of Vietnam, through her role as a dissident in the First Indochina War, to her exile, and the pivotal moment when she embraced sculpture. Across multiple projections, the installation unfolds as a story of dispossession, resistance, and colonial violence. In excavating the life of Thi, Nguyen Phan revives erased fragments of Vietnamese history, weaving them into a collective memory and mythology.

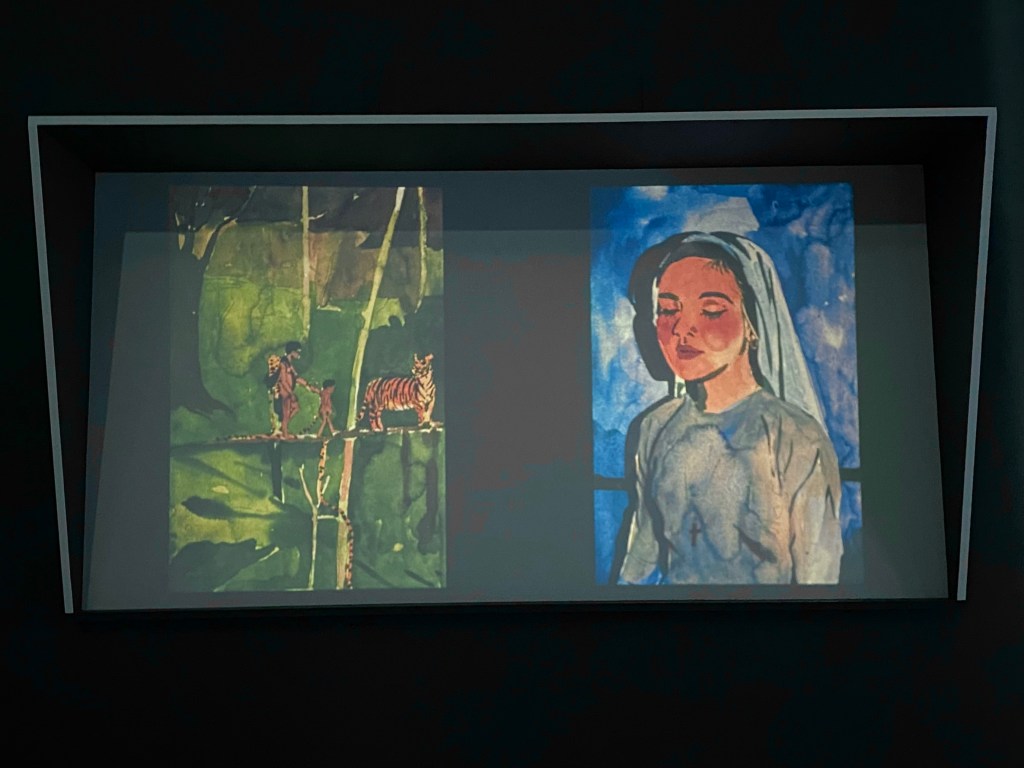

Nearby, her work Forêt, Femme, Folie appropriates photographs by Jacques Dournes, a French missionary who “studied” the Jaraï people under the guise of ethnology. In Nguyen Phan’s altered slides, a man first appears as Dournes captured him, only to reappear seconds later with the head of a tiger, delicately painted in watercolor. By hijacking the supposed objectivity of the colonial gaze, she exposes its fictionality, suggesting that “rational” rhetoric is no less fabricated than folktales.

Following the same vein, Voyages de Rhodes juxtaposes watercolors with the writings of 16th-century Jesuit Alexandre de Rhodes. The installation spreads across a wall, its frames tilted and unevenly disrupted in order, creating a chaotic hanging uncommon to find in white cubes. One page reads “white optimism,” a phrase that contrasts sharply with De Rhodes’s account of converting listeners not through reason, but through tears—an episode revealing the paternalism embedded in colonial discourse, however “logical” it pretended to be.

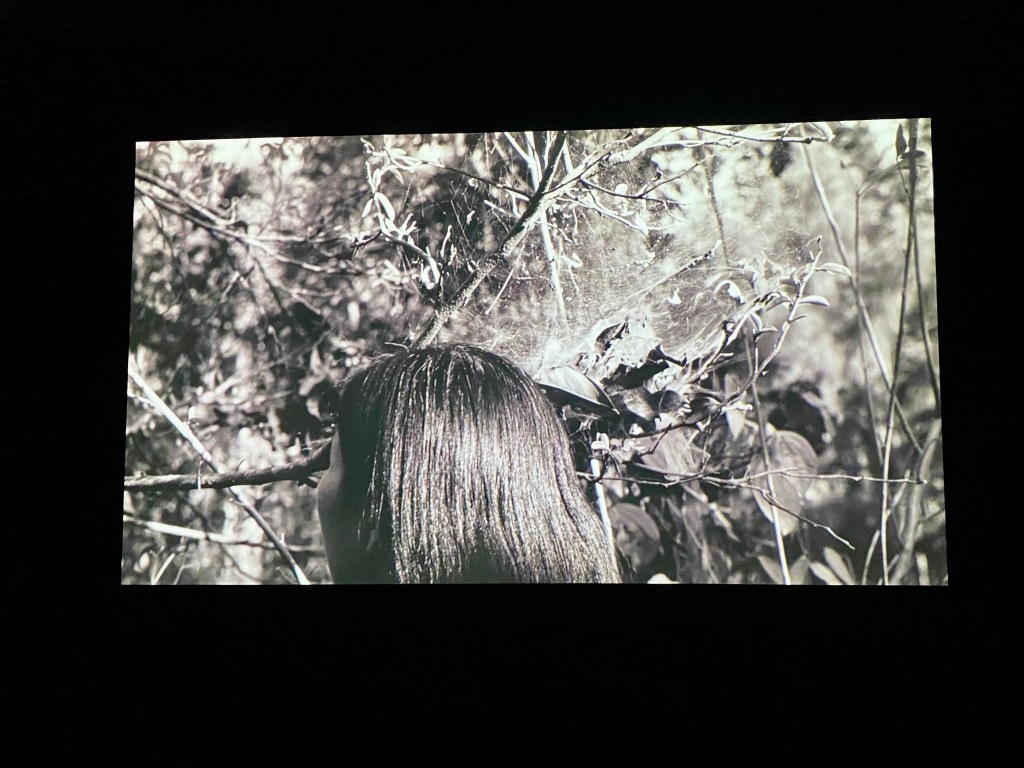

Throughout, Nguyen Phan questions Western universalisms—particularly Cartesian logic—by reclaiming the landscape as an aesthetic and narrative force with agency. In her video cycle Palm-of-the-Hand: Moving Image, nature is not the backdrop but protagonist. Characters play beneath spider webs, drift along rivers, or read in the jungle undergrowth. Here, nature is not perceived as a resource to be exploited but as a being with its own right to exist, challenging extractivist relations and offering a relational vision.

Colonial legacies reappear in subtle but piercing ways. In Voyage de Rhodes, watercolor inscriptions of crops—sugarcane, rice, corn, rubber—evoke the monocultures imposed under colonial rule, which homogenized landscapes and depleted soils. Although the plantation as such is no more, its effects linger in today’s diets, a reminder of the system’s endurance. Likewise, Untitled (Heads)—a curtain of jute fragments and bronze heads—recalls both the sacred Ma Mot tree used in Vietnamese rituals and the famine of 1945, provoked by Japanese occupation and later silenced in official history. Like a talisman, the piece ties together agriculture, the sacred, memory, and loss.

Time in Nguyen Phan’s work resists linearity. Rather than a march toward progress, her temporalities bend and overlap. In Palm-of-the-Hand: Moving Image, the camera wanders through a park that once served as a prison, while a voice recalls the story of an inmate. Past and present interlace, with legends, memories, and lived experience coexisting in the same continuum. Orality becomes vital, sustaining memory and connecting generations, just as in Yasunari Kawabata’s Palm-of-the-Hand Stories, which inspired her. Here, time is affective, not economic; lived, not measured.

Her work is also deeply sensual—not in subject matter but in approach. In Reincarnations of Shadows, hands glide over papayas, feet press into dry leaves, hair ripples across a wooden floor. The body mediates perception, dissolving the split between reason and sensation. In the third exhibition room, sculptures by Diem Phung Thi rest across a table. Their geometric forms, polished yet organic, echo bodily presence, inviting haptic contemplation.

Beyond the exhibition hall, a work by Truong Cong Tung bears the phrase: “I heard it said: my eyes lie to me, they forget, they do not know how to see what is real.” Attributed to a Jaraï inhabitant, it questions the supremacy of sight, long tied in the West to notions of truth. Vision, Nguyen Phan reminds us, deceives as easily as it reveals. Her exhibition dismantles the certainties of modernism, opening space for multiple narratives and peripheral voices.

Her stories do not claim authority; they “speak nearby” rather than about. They dwell in margins, attentive to blind spots and silences, as in her Ode to the Margins, a garland woven of bamboo by the Bana people. Her art arises from chasms, where darkness meets light.