Quiénes nos subieron el dolor

de esas montañas se van diciendo las inmensas

praderas del cielo … Somos todos los pastos de

este mundo les contestan

Raúl Zurita, Primer canto de los ríos.

In the last ten years, we’ve seen an increasing interest in textile artworks. Artists such as Anni Albers, Sonia Delaunay, Sheila Hicks and more seized the medium, introducing crafts into the fine art canon. But it was not until the 1970s that textile became an ally for feminist artists, a political space where women could challenge patriarchy. Inheriting from these pioneers and mother figures, Antonia Alarcón’s work continues where previous textile artists left off. Her work, inhabited by a pastel color palette and embroidery, may at first glance seem “girly” and candid. However, each piece is both personal and political: an account of the artist’s journey and her relation to place.

Born in Chile in 1994, a few years after the end of the dictatorship, she migrated to Mexico at a very young age. This “dislocation,” as she calls it, has fueled her work, leading her practice toward themes of landscape, labor, poetry, community, and sheltering.

Her exhibition Con mi dedo trazo el camino del agua at Museo Carrillo Gil in Mexico City presented a nest-shaped piece designed to invite viewers into dialogue on climate change and its effects. Connection with her audience has been key for Alarcón. Her role as a teacher and workshop coordinator has made her particularly attuned to transmission — of skills, memory, care. Just as important is her connection to her heritage, her motherland, her kinship. Donde crecen los claveles, for instance, is dedicated to her mother and to Chile: two translucent fabrics bear red flowers suspended above the ground, while beneath them lie red carnations. The piece alludes to victims under Pinochet’s regime and the collective process of grief. What is the impact of such wounds on memory? How can we live in the present while still honoring our ancestors? To find answers, Alarcón sought inspiration in Chile’s arpilleras — dissident women who stitched patchworks during the dictatorship to sustain their families. Their sewing was survival, but also defiance: textiles became an extension of their bodies, stitching together protest and hope.

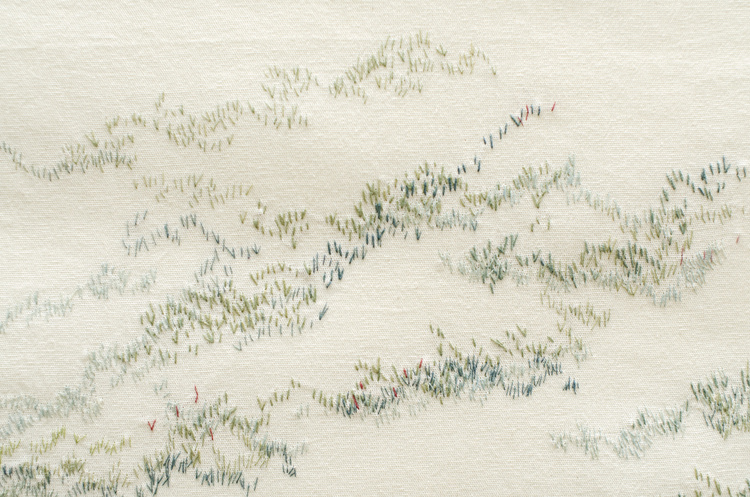

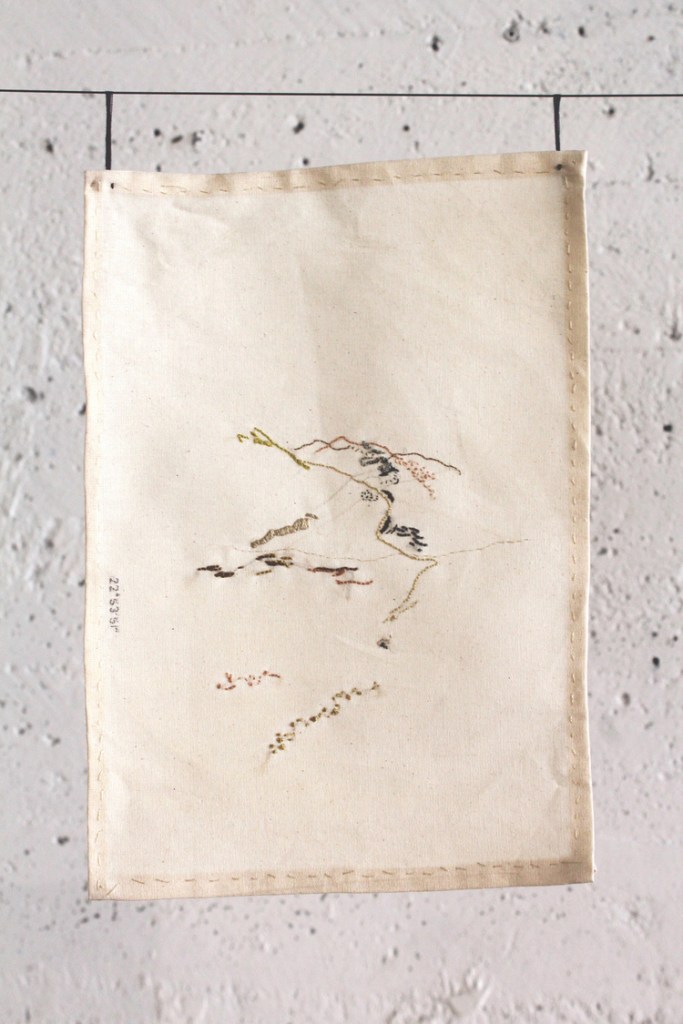

For Alarcón too, embroidery is tethered to the body. When recalling her first encounters with textiles, she evoked the image of a scar healing, thick like a seam: “my body was seaming.” Cloth, like skin, holds memory. For her, the medium became a second epidermis, porous and fragile. This relation extends to her sense of belonging. Accustomed to Chile’s topography — its sea, its Andes — she felt engulfed upon relocating to Mexico. To survive, she began embroidering maps, transforming vast territory into tangible cartographies. In Atlas de memoria, abstract landscapes unfold as threaded memories, each line a trace, each stitch a latitude. Though elusive, these maps anchor her story to the earth, locating her both symbolically and literally.

Moreover, textile bridges her past and present. It offered a refuge from Mexico City’s frenzy, a world within a world where threads obeyed their own rhythm. “There is a specific way of creating textiles, and this is deeply connected with how humans experience the world.” In opposition to capitalism’s logic of speed, mass production, and disposability, Alarcón embraces slowness and care. Even her threads are dyed naturally, in collaboration with plants. She calls them “collaborators,” extending agency beyond humans, questioning our place in the natural order, and reflecting on the climate crisis.

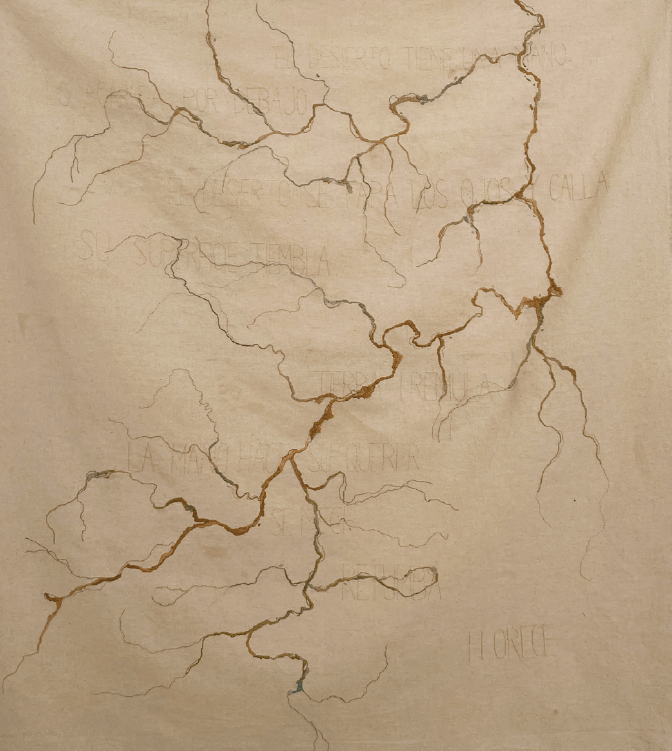

Alarcón’s pieces are not mere textiles but cartographies of grief and migration. Her series Todos los pastos del mundo depicts the flows of humans, animals, and plants across the Mexico–U.S. border. Here, motion is not uniquely human: seeds, spores, winds, and waters cross as freely as people once did. Political boundaries falter before natural cycles; landscapes reveal themselves as unstable, alive. Her collaboration with the project Atlas Transgression makes this explicit: stitches become signs, cartography becomes testimony. A black square denotes the far right in Montréal; a blue one, cannabis dealers. These “tryspaces” map vulnerability, showing the fragility and diversity of urban experience.

Faithful to her working process, Alarcón gives voice to the vulnerable, human and more than human. In contrast to photography’s claim to “truth” — long contested by thinkers like Susan Sontag, Jacques Rancière, and Judith Butler — Alarcón’s textiles whisper subtler truths. They resist the spectacle. Violence is not absent; it is buried in stitches, waiting to be unearthed. La Promesa recalls the migration of coffee plants and, with them, African culture in Mexico, culminating in son jarocho folk music. Here, threads evoke colonial routes; poetry accompanies them, inviting the viewer to imagine alternative futures. The spectator is not passive: they complete the circuit of meaning.

If her works solicit the spectator’s body, they also engage the mind. Her practice thrives on symbolism, on ambiguity. Landscapes do not represent exact places, but rather memories, sensations, questions. In Sedimentación ósea, she takes up a legend that one’s bones adapt to a topography after seven years. Though unverifiable, she embroidered this myth into white fabric, envisioning cloth as bone, fragility as structure. In her accompanying text Instrucciones para leer un cuerpo, she wondered: “What latitude has shaped my bones?” Fact and fiction blur into a poetics of embodiment.

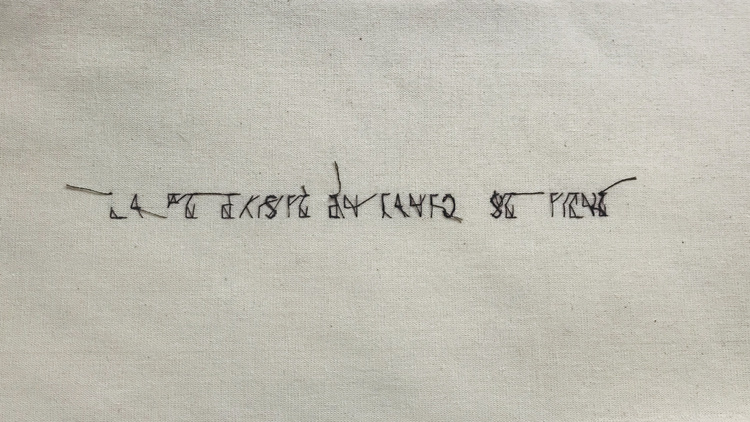

Her interest in language continues in Se me hace tarde para volver, where stitched aphorisms speak of displacement and belonging. These works link her to Chile’s poetic tradition, with references to Raúl Zurita, Jorge Teillier, Violeta Parra, and Gabriela Mistral. Poetry, like textile, became a clandestine tool during oppression — a subterfuge, a secret passage. Zurita’s dense poems denounced dictatorship through hermetic imagery; Alarcón, while less opaque, carries a similar weight. Each stitch, each verse becomes a fragment of grief, a compass pointing south.

In La promesa, a poem tells of an entity who follows a “promise” across mountains, destination unknown. This echoes Alarcón’s own migration to Mexico: uncertain, but persistent. Poetry here is not only mourning but reconstruction — a space of utopia and possibility. In Loa a la tierra, the land itself speaks in verse, breathing through trauma, transforming silence into song.

“In the particular is contained the universal.” Alarcón’s textiles narrate dislocation but extend toward collective experience. Migration, exile, climate change — these are the movements of our time, shared by humans, animals, even rivers. For her, body and landscape are one: stitched, porous, scarred, resilient. With each embroidery she embraces life’s fragile seams, echoing her own fractured body and soul. She is against walls and fences; she is for collaboration, exchange, conversation. Poetry offers solace. Thread becomes breath. She stitches to endure, to outlast our fleeting existence.