En la energía de la memoria

la Tierra vive

y en ella la sangre de los

Antepasados

¿Comprenderás, comprenderás

por qué –dice

aún deseo soñar en este Valle?

Elicura Chihuailaf, Aún deseo soñar en este valle

For the Mapuche people, blue is a sacred color signifying endless skies, flowing waters, powerful cascades, and the vigor of the sea. It also represents intangible forces — the things we cannot see and which dwell in the afterlife. It is therefore unsurprising that this color is ever-present in Seba Calfuqueo’s body of work, a Mapuche artist who places their people’s culture at the center of their artistic practice. Working across a myriad of mediums — from video, photography, and 3D rendering to installation and performance — Calfuqueo uses these forms of expression to tell Mapuche stories and to bear witness to their people’s efforts to endure.

Their work celebrates the memory and struggles of their people over the past centuries. For example, in one of their videos titled Tray Tray Ko (2022), Calfuqueo is seen descending toward a cascade. They carry a shimmering blue mantle through the woods, while the sound of bells — hanging from their hair — punctuates each movement, giving rhythm to the scene. The landscape is lush and verdant; as they approach the waterfall, their body merges with the cascade, creating a unified entity. In the artist’s vision — and by extension, in the Mapuche worldview — nature and humanity are not to be separated, but rather regarded as an intertwined organism, a web of entanglements connecting all beings. Territories, landscapes, and nature are breathing entities that escape rigid categories. They move and change over time, contradicting outdated conceptions such as natural selection or competitiveness within the “natural” sphere. Another of their works, Spores (2021), shows the artist in the middle of a forest surrounded by trees, rivers, and stones, emphasizing the synergy between ecosystems and human bodies.

Furthering this idea, their video Kowkülen, Liquid Being (2020) shows Calfuqueo lying in a forest stream, wearing nothing but a blue rope tied in the shibari style. The water flows and the current rocks their body, carrying it toward an unknown destination. As we watch this dance, we become aware of the status of water in Chile. Since 1981 — when the current constitution was written, during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship — private ownership of water has been protected, making Chile the only country in the world where water rights are treated as private property. Regarded as both a sacred element and a spirit, water recurs throughout Calfuqueo’s work. Its non-binary nature fascinates the artist, yet its commodification also compels critique, revealing their political stance on the issue. For Calfuqueo, water and landscape at large are not merely aesthetic subjects or motifs to be reproduced; they are “territories in dispute,” much like non-binary and female bodies. As such, they form part of an intrinsically political system that has stripped the Mapuche of their land.

In his book The Time of the Landscape: On the Origins of the Aesthetic Revolution, French philosopher Jacques Rancière asserts that a landscape always reflects a political and social order; even something as seemingly innocent as a garden conveys a political vision. He cites the French garden as an example: with its geometric forms and manicured hedges, its layout mirrors France’s absolutist monarchy, imposing hierarchy within a supposedly natural setting.

In the same manner, Calfuqueo’s portrayals of nature reveal a world inhabited by unseen forces, challenging binaries and fixed categories that sustain colonial notions of nature and gender. A testament to this is their video The Quilas (2021), where the artist’s body, filmed at night, merges with the quila — an endemic plant that is hermaphroditic and bisexual. According to the video, this plant impeded full colonization of the forest by creating natural barriers; its strength and resilience parallel the Mapuche’s resistance to Western morals and their enduring survival.

Following this thread, Calfuqueo’s work Kangechi (2019) explores the relationship between hair and gender. Having attended a military school, the artist experienced the hardships of a strict and patriarchal education. Hair often became a site of conflict, symbolizing social status, gender identity, and the struggle to thrive within a hostile environment. Kangechi, which translates as “the other” or “queer” in Mapudungun, embodies the artist’s attempt to counter their upbringing by presenting hair as a record of their Indigenous heritage — a sign of strength, tenderness, and power. Thus, hair becomes a transgressive space of reflection, a political statement that affirms non-heteronormative identities.

Their performance Bodies in Resistance (2020) extends this idea, treating gender as an imaginary construct inherited from Spanish colonization and used to silence Indigenous populations. Emphasizing nature’s fluid essence, Calfuqueo’s work challenges the status quo, offering “open-ended gatherings” guided by alternative rhythms that engage the viewer’s senses. Works such as La Funga (2021) are built around smell rather than sight, subverting the latter’s hegemonic dominance — which, for Calfuqueo, is deeply influenced by colonial standards.

Seba Calfuqueo’s work invites us to enter the Mapuche worldview and reconsider our relationship to nature and otherness. By reclaiming myths, they weave together politics, fiction, Mapuche storytelling, and nonfiction, giving rise to new narratives where the collective becomes the central force. Working collaboratively through projects such as Rangiñtulewfü and Espacio 218, Calfuqueo conceives of art as a realm of possibilities — a communal space that transcends borders and reaches audiences beyond the contemporary art circuit.

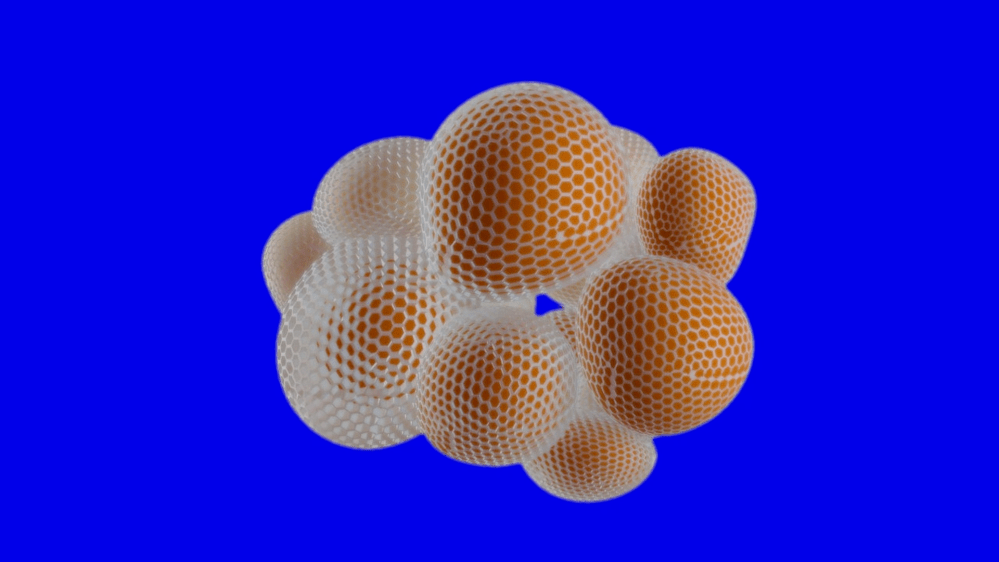

These alternative rhythms emerge again in Mapu Kufüll (2020), a video that delves into the “Pacification of Araucanía” — a series of military campaigns and settlements by the Chilean army that resulted in the incorporation of Araucanía into Chilean territory. During this difficult period, mushrooms became an essential food source for the Mapuche and were later integrated into their cosmological beliefs. The video follows a forager searching for mushrooms; as the character teaches us about their anatomy and proper harvesting techniques, we are invited to imagine alternative ways of relating to nature.

Every element in the artist’s work is deliberate. The use of 3D technology in Mapu Kufüll, for example, carries symbolic weight. Indigenous art is often expected to consist of textiles, ceramics, or jewelry — traditional crafts — but by embracing digital tools, Calfuqueo redefines Mapuche aesthetics, asserting their place in contemporary artistic discourse. Through works like this and Ngürü Ka Williñ (Fox and Otter) (2022), the artist envisions a future for their people, projecting them into times ahead.

Seba Calfuqueo’s work invites us to enter the Mapuche worldview and reconsider our relationship to nature and otherness. By reclaiming myths, they weave together politics, fiction, Mapuche storytelling, and nonfiction, giving rise to new narratives where the collective becomes the central force. Working collaboratively through projects such as Rangiñtulewfü and Espacio 218, Calfuqueo conceives of art as a realm of possibilities — a communal space that transcends borders and reaches audiences beyond the contemporary art circuit.

Ultimately, their work revisits ancient myths and relocates them into our current time. What we learn along the way is that we are still mythical creatures, we still use mythology and tales to explain ourselves. Myths continue to give meaning to our existence; the world has yet to unveil epic narratives.

Sources:

Brand New Ancients, Kae Tempest, Picador, 2013

De sueños azules y contrasueños, Elicura Chihuailaf, Editorial universitaria, 2018

Habiter en oiseau, Vinciane Despret, Actes Sud, 2019

Le temps du paysage, Jacques Rancière, La fabrique éditions, 2020

The mushroom at the end of the world. On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Princeton University Press, 2017

#sebacalfuqueo #galeriapatriciaready #elicurachihuailaf #mapuche #contemporaryart #art #video #performance #jacquesranciere #annatsing #vincianedespret