At the dawn of time, when animals, trees, rocks, and other elements of the world were still non-existent, the gods took it upon themselves to create life—and with it, humanity. The first humans, however, were not considered worthy of their creators, for they lacked substance. The gods thus produced successive versions until humans could properly think and speak. So begins the Popol Vuh, a sacred text recounting the creation myth of the K’iche’ people, one of the Maya communities of Guatemala. More than a foundational myth, the Popol Vuh endures as one of the few surviving works of pre-Columbian literature—a rare and profound window into the K’iche’ Maya worldview: their past, present, and, to an extent, their future.

Artist Edgar Calel, a Maya Kaqchikel from San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala, draws from this ancestral heritage, using his artistic practice as a means of traveling across time and space to expand our understanding of Kaqchikel beliefs and traditions. His prolific body of work—ranging from photography and performance to textiles and drawing—addresses questions of transmission, collective memory, the power of language, and resistance to systemic violence.

In his piece B’atz: Weaving Constellations of Knowledge, Calel appears wearing a blue sweater inscribed with the names Itza and Ixil, both Mayan languages. In total, the garment bears the names of the twenty-three Indigenous languages spoken in Guatemala, transforming the artist’s body into a living celebration of linguistic diversity. By foregrounding these languages, Calel reinforces the bonds among Maya communities and asserts their importance as essential vehicles of knowledge and world-making. As he states, “Knowledge comes from languages; it comes from our ancestors’ collective memory, and by speaking them, we keep our community’s memory alive.” In the words of Donna Haraway, “It matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what concepts we think to think other concepts with.” Calel’s work embodies precisely this recursive storytelling process, in which language itself becomes both the medium and the message of cultural survival.

Calel’s practice also explores how memory can be preserved and celebrated through ritual and collective action, as seen in his performance and installation Ru k’ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el (The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge). This work centers on the creation of a shrine that connects the artist with his ancestors. Calel invited members of his village to participate in a ceremony in which each person contributed fruits, liquor, pine, and musical instruments. The fruits were placed on stones carried from a nearby river by Calel’s grandparents—objects that, for the artist, embody ancestral strength and memory. “At some point in their lives,” he explains, “they felt the weight of each stone; the stones hold the memory of my grandparents’ bodies but also of other beings that once used them as shelter.” Through these materials—stones, fruits, liquor, and pine—Calel constructs vessels of communication between worlds. The performance collapses temporal boundaries, connecting participants to a timeless territory where past, present, and future coexist.

For Calel, shrines and installations serve dual functions: they are both acts of communion with his ancestors and acts of artistic creation. He perceives no separation between ritual and art; both share the same guiding principle—the creation of dialogue through symbolic action. His approach challenges Western conceptions of the artist as an autonomous individual whose work is detached from community and collaboration. In contrast, collaboration lies at the core of Calel’s practice, often involving his family, community members, or other Indigenous peers.

One notable example is Uelf-Tzamiy-Jjichan / Tierra-cabello del maíz tierno-peine, a work produced in collaboration with a Guaraní artist from Brazil. The piece depicts Calel holding an Afro comb intertwined with corn silk, set against a field located at the border of Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina. The composition invites reflection on three intersecting cultural identities: the African (symbolized by the comb), the Guaraní (represented by the land), and the Kaqchikel (embodied by the corn silk and Calel’s hand). Although Calel retains authorship, he emphasizes the work’s collaborative genesis, situating it within a broader network of Indigenous and diasporic exchange.

Collective creation also becomes a strategy of resistance against hegemonic power structures. In B’atz: Weaving Constellations of Knowledge, Calel deliberately reclaims the Indigenous image: “Oftentimes we see photographs of Indigenous people taken by foreigners. In this photograph, I wanted to reverse that trend and condemn such practices, as well as the systems that sustain them.” By assuming control over the act of representation, Calel subverts the colonial gaze that has historically exoticized Indigenous bodies, echoing the exploitative anthropological photography of earlier centuries. While acknowledging an improvement in the living conditions for Indigenous communities, the artist recognizes that systemic violence continually reconfigures itself in new forms.

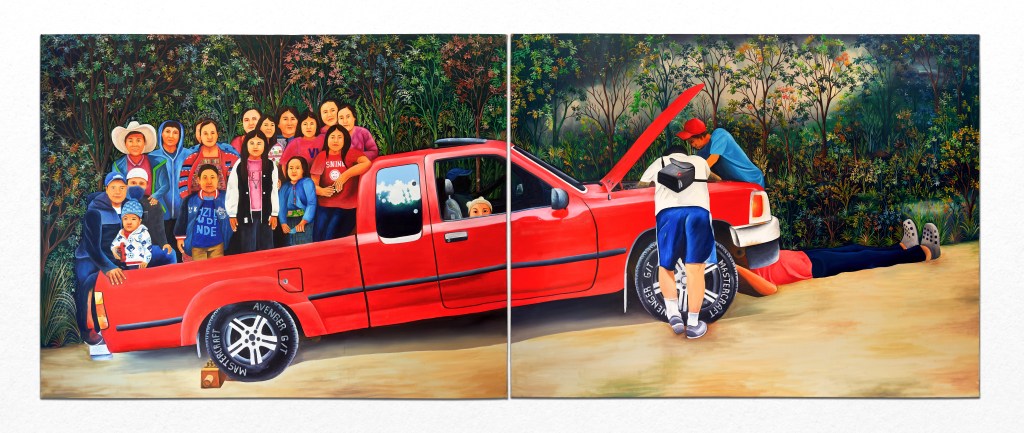

This awareness is also evident in Ru raxalh ri Rua Ch’ulew (The Greenness of the Land), a painting depicting members of Calel’s family gathered around a damaged red truck surrounded by lush vegetation. Some figures repair the vehicle while others pose for the scene. The work offers a contemporary portrait of daily life within Calel’s community, asserting an Indigenous presence grounded in the present rather than confined to the past.

Calel’s art resists anthropological interpretation; it does not aim to document Kaqchikel life but to tell stories—“carrier bags,” in Ursula K. Le Guin’s sense—capable of remaking history and holding worlds together. His works function as speculative narratives in which ancestral beliefs coexist with contemporary beliefs and technology, projecting Indigenous futures that defy temporal and epistemic marginalization. Through his practice, Calel not only denounces the enduring violence inflicted upon his community but also re-centers art as a communal act of remembrance, dialogue, and renewal. His installations and performances unearth stories long silenced, creating spaces where suppressed voices can be heard and where traditional notions of art and authorship are reimagined. In doing so, Calel opens pathways toward new ways of perceiving and inhabiting the world.

Sources:

K. LE GUIN Ursula and HARAWAY Donna, The Carrier Bag Theory, Ignota, 2019

#edgarcalel #kaqchikel #guatemala #proyectosultravioleta #contemporaryart #art #installation #performance #ritual #donnaharaway #ursulakleguin #carrierbagtheory #decolonization